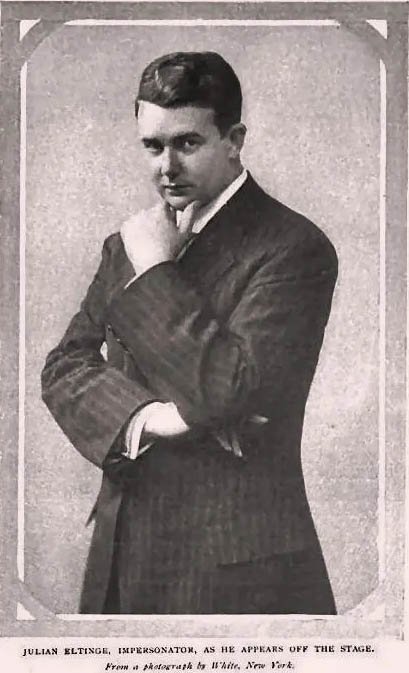

Drag Queen and LGBTQ Icon Julian Eltinge

The Greatest Gender Bending Star of All by Duane Scott Cerny

Table of Contents

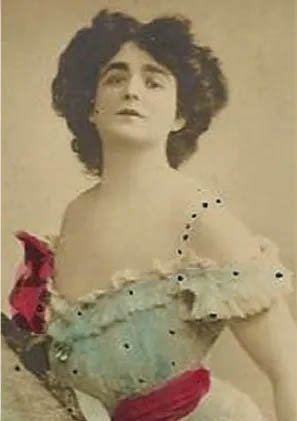

LGBTQ icon and drag queen Julian Eltinge an introduction

Early Career and Rise to Stardom of drag queen Julian Eltinge

The Eltinge Theater

Personal Life and Legacy

Influence on Entertainment

Drag Queen Julian Eltinge’s influence on the twenty-first century

LGBTQ Icon Julian Eltinge’s Death

LGBTQ icon and drag queen Julian Eltinge an introduction

Here’s a fun party game:

Guess six Broadway Theaters named after celebrated Broadway luminaries. Ready?

The Gershwin, of George and Ira fame

The Helen Hayes, First Lady of American theater

The August Wilson

The Neil Simon.

The Steven Sondheim

But who’s the 6th?

How about Julian Eltinge? Who, you may ask? They were never on Drag Race, but is Julian Eltinge the most famous drag queen of all time and an LGBTQ pioneer?

Probably the most famous unknown actor who ever died a famous actress… and vice versa. Let’s start with this riveting fact: Dorothy Parker invented the word “ambisexual” to describe Julian Eltinge. Exactly how famous must you have to be for Dorothy Parker to create a word just for you?

Early Career and Rise to Stardom

Born in 1881, by the age of ten Julian Eltinge was appearing onstage in feminine attire and wowing audiences not only with his coquettishly brilliant acting skills but his accomplished vocal abilities. He first appeared on Broadway in 1904 and though hardly an overnight success, his guise as a convincing woman soon began setting box office records on the vaudeville circuit with his one man/woman parody of the Gibson Girl called The Simpson Girl. European tours brought him international stardom, followed by a fawning Hollywood.

The Eltinge Theater

So illuminating a star was Eltinge that legendary theatre architect Thomas W. Lamb designed what he’d hoped would be a lasting edifice to the most famous female impersonator on the planet: the Eltinge. Built in 1912, the beaux arts theatre is still on 42nd Street—well, sort of. The structure was moved some 200 feet from its original location, where it now serves as the façade and lobby of the AMC multiplex. The lobby remains somewhat intact, with a ceiling fresco detailing the three muses, all Eltinge in elegant lady’s attire. Sadly, the artist himself never played at this theatre, but that’s only another strange twist in the life and cross-dressing times of Julian Eltinge.

Personal Life and Legacy

In 1920, Eltinge appeared as a woman (of course) opposite Rudolph Valentino in the film The Isle of Love, just one of some dozen films in which he would star. Rumors of a bicoastal affair bounced about, although in what gender variance or role reversal of sex/romance no one said, least of all Valentino or Eltinge. Sometimes love is blind, especially when you have a giant bonnet pulled over your wig while singing a tune about virginal splendor.

But who was Julian Eltinge? Though now mostly forgotten, in his time he was one of the most original creations the entertainment world had ever seen: the iconic, one-named wonder Eltinge! He successfully branded himself with not only with a namesake theater, but also a magazine: Julian Eltinge’s Magazine of Beauty Hints, in which he offered make-up and lifestyle suggestions to his adoring fans of both sexes and sold his own brand of beauty products.

At the height of his fame, Eltinge was one of the highest-paid actors in both film and on the Broadway stage. He parlayed his self-styled musical comedy “The Fascinating Widow” into a financial empire, playing both the smooth-talking college boy and the virtuous virgin— to this day, an acting stretch by anyone’s imagination. Consider that some seventy years before the film Tootsie would appear as legitimate cross-dressing entertainment fashion, Eltinge had virtually invented the genre.

Influence on Entertainment

He somehow seduced both himself and a national audience with an inexplicable, yet convincing magic trick of sliding sexuality. Even though the early twentieth century was a more innocent times, people were no more accepting of a drag queen and LGBTQ pioneer like Eltinge. His perpetually closed closet door did much to shield the public from his private life; however, his overtly feminine, over-the-top public persona was very much the lady fair. Perhaps that same closet door, so filled with gorgeous gowns and fabulous frocks, could never be fully opened against the floodgates of his fashions. In effect. Eltinge was an ingenue of a genie that once released could never be put back in the bottle—perfume, gin, or otherwise.

Little is known of his personal life, and by all accounts he hid his sexuality from a speculative media. He built a magnificent home in Hollywood, the pink Villa Capistrano, where he lived with his mother. Insert stereotypical rumors here.) But beyond this, there is silence–- and not just in film. The tabloids had him engaged him to countless starlets, and he loved to toy with the press. Once, to prove his manhood, he staged a boxing match with “Gentleman” Corbett. By most accounts, it was a draw… most probably of attention.

Perhaps not so curiously, he often found himself in innumerable fistfights with both stagehands and drunken cabaret patrons, ever demanding that his masculinity remain unquestioned. However, it was hard to pull this off when his stage monikers ranged from “The Crinoline Girl” to “Mr. Lillian Russell.” He must have given his ever-struggling press agent quite the ulcer.

An impossible persona to typecast, Eltinge greatest gift was perhaps his ability to not merely play a woman with complete believability but to also convincingly become one, which is why audiences claimed he was one of the greatest living actresses of his time. For Eltinge, it wasn’t so much an act as a metamorphosis.

Drag Queen Julian Eltinge’s influence on the twenty-first century

Today, Eltinge’s influence on the twenty-first century is all around us, though you have to squint though some rather thick false eyelashes to see the cross-dressing ghosts.

Do you remember Julie Andrew’s final wig reveal in Victor Victoria? Not only did Eltinge invent that signature move, he virtually trademarked it throughout his career-- and not at some drag bar but through a long and notable vaudeville career and concert appearances around the world.

There are numerous references to the Eltinge Theatre in Douglas Carter Beane’s play The Nance. Though the theatre itself was a legitimate vaudeville house, by 1939 it had slipped into its darker (see: seedier) burlesque days. Mayor LaGuardia did his best to shut it down or at least limit the activities of single men in the darkened upper balconies.

“Alex, may I have Actors who played both male and female parts in the same play or film for one hundred?” Um, Charles Ludlum, followed by Charles Busch, Dustin Hoffman, followed by… whom? It’s a short list of drag queens and other performers. Eltinge, on the other long glove, simultaneously played both sex roles so realistically that audiences often thought he had a body double. Yet if this was the one masterful trick of his career it was an incomparable one.

Female impersonators, drag queens, and LGBTQ icons such as Charles Pierce would later channel the star stylings of Mae West, Betty Davis, Tallulah Bankhead, the list is endless—yet that was not Eltinge. He was not a female impersonator in the classic sense but rather played characters as an actress; he was an actor playing a woman that just happened to be him/herself. In a fashion, Eltinge set the stage for the most famous male drag queen of the twentieth century: Harris Glenn Milstead, aka “Divine.” Still, the great distinction is that Divine played it all for comic effect, whereas Eltinge was, mostly, coquettishly serious. In his silent pictures, title cards often revealed the laugh with barely an eye roll from Eltinge.

LGBTQ Icon Julian Eltinge’s Death

Eltinge’s final performance was at Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe nightclub in New York City in February 1941. He died ten days later at his apartment on West 74th Street. His death, like his much of his personal life, remains a mystery, leaving behind a bustle full of questions and, undoubtedly, many spectacular black veils.

—This article was written by Duane Scott Cerny and is a chapter from his acclaimed book, Vintage Confidential.